Posted by Hania Oleszak and Mari Hackbarth, Jefferson County Extension

With summer finally in full swing, we’ve been wading knee-deep in plant and insect samples over at the Jefferson County Plant Diagnostic Clinic. With that in mind, we thought it would be fun to clue you in to some of the pests and diseases that we’ve been seeing lately. See if you can identify any of the following samples as we walk you through some of the key steps of our identification processes…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Our first culprit is a first to our clinic. With a piercing,

sucking mouthpart originating from in front of its eyes and long, segmented

antennae, this insect appears to fall under the Hemiptera order.

Bee Assassin

Bug; photo credit: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University

This sample came with a critical piece of information for its identification: the environment in which it was found. Specifically, this insect was found attacking a honey bee near a hive.

Our next culprit makes its way, unfortunately, into our

clinic a handful of times a year. Like the bee assassin, this sample was also

identified to the Hemiptera order, which is also the order referred to

as “true bugs”. Additionally, this

sample was found in an assisted living facility bedroom…any ideas yet?

Bedbug, Cimex Lectularius dorsal view; photo credit Pest and

Diseases Image Library,

Bedbug, Cimex Lectularius ventral view; photo credit Gary

Alpert, Harvard

Note: the piercing, sucking mouthpart originating from in front of the eyes and the long antennae broken into 4 segments.

What’s the final verdict? It’s a bed bug (Cimex

lectularius), ew! Bed bugs are bloodsucking insects, often feeding in the

middle of the night. They do not transmit disease. People often develop red, itchy swellings

from bed bugs, but these bites alone are not enough to diagnose a bed bug

problem. Identification requires microscopic

examination of the beak length, antennae and pronotal hairs. Bed bug interceptors, basically traps that

bed bugs can’t climb out of, can be placed underneath the bed post in order to

monitor for bed bugs.

Next up, we have a raspberry plant that was brought in for

management advice. This sample already had been diagnosed upon entering the

plant clinic, but we won’t give you the answer that quickly! The key symptom in

this diagnosis is that the shoot tips of the raspberries are wilting. Additionally,

there are two rows of punctures along the stem, beneath the point of wilting.

Spoiler alert: these two rows of punctures are actually made by female Raspberry cane borers (Oberea perspicillata), surrounding the point at which eggs have been laid in the pith of the raspberry cane. Upon hatching, larvae burrow down through the pith, making it down about an inch or two from the punctures by the first winter, and eventually making it down to ground level. To control for the Raspberry cane borer, it’s best to prune the raspberry canes below the puncture marks, or as far down as there is evident damage to the pith of the cane.

Raspberry Wilting; photo credit: Mark Longstroth, MSU

Extension

Raspberry Cane Borer Larva; photo credit: Alan T. Eaton

Next in our line-up is a crabapple tree with an array of symptoms that are quite telling and commonly seen in our clinic. Looking at the crabapple branch, we could see darkened, mummified fruit, as well as blackened and crooked shoot tips (which we refer to as shepherd’s crooking).

Shepherd’s crooking symptom of Fire blight; Photo credit Don Hershman, Bugwood.org

Upon further investigation in the lab, we could see under

the microscope that there was bacterial streaming (i.e. the movement of bacteria

out of the cut tissue) present in the fruit. Watch a youtube video of bacterial

streaming HERE. So cool! This confirmed our suspicion that this

crabapple tree has…Fire blight! Fire blight is a bacterial disease, caused by

the bacteria Erwinia amylovora, that affects members of the rose family.

The bacteria can be spread by insects, rain, or contaminated pruning tools,

which is why rainy springs are conducive to the spread of Fire blight and why

we recommend to disinfect pruning tools between every cut when working with

plants of the rose family. Blossom blight (blackened, dead flower blooms) and

oozing exudate from the tree or fruit are other tell-tale signs that your plant

may have Fire blight. Unfortunately, there is no cure for Fire blight, so it’s

best to prevent the spread of the disease and remove infected plant parts.

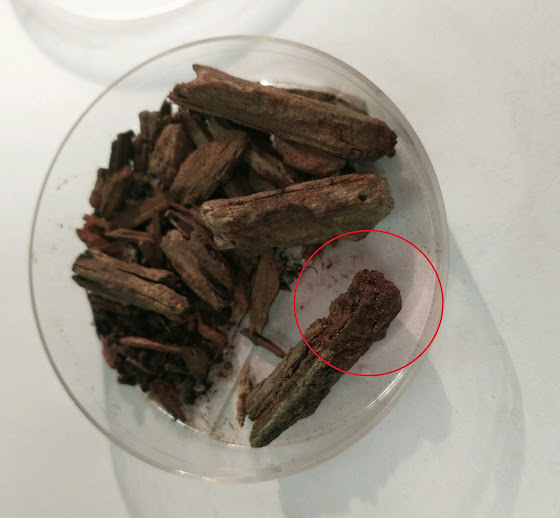

Last, but not least, is the grub that got away! Late one

afternoon, we received a sample of a grub that was found in a mulch pile and placed

it, along with some mulch, in a closed petri dish overnight. To our surprise,

the grub was nowhere to be found the following morning – all that remained in

the petri dish was mulch (see below).

Photo credit: Mari Hackbarth, Jeffco Plant Diagnostic Clinic

Rastral Pattern on Grub; photo credit: Mari Hackbarth

Interestingly, bumble flower beetles form oval, earthen pupal cases as they mature into their adult forms and, looking more closely at second sample, we were even able to find some (see below)!

Bumble Flower Beetle Larvae and Pupae; photo credit: Mari

Hackbarth

Wait a minute! If

bumble flower beetles form pupae that look like big chunks of soil, and if our

initial grub that got away looked very similar to the bumble flower beetle

grubs…could our initial grub actually still be hiding in our petri dish in a pupa?

What do you think?

References:

- https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/biological-control-information-center/beneficial-predators/assassin-bug/

- https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/assassin-bugs-and-ambush-bugs-reduviidae/

- https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/galveston/beneficials/beneficial-08_bee_assassin_bug.htm

- https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/insects/conenose-bugs-kissing-bugs-and-insects-of-similar-appearance-in-colorado-5-624/

Fire Blight:

· https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/yard-garden/fire-blight-2-907/

Bumble Flower Beetle:

· https://entomology.unl.edu/turfent/documnts/wgrubs.shtml

· https://extension.usu.edu/pests/ipm/notes_ag/veg-bumble-flower-beetle

· https://extension.usu.edu/pests/uppdl/files/factsheet/bumble-flower-beetle2011.pdf

Do you still have the sample so you can see if the pupal form is in there?

ReplyDeleteWe do - we're waiting to see if, in time, it pupates!

Deletethis is a great Co-Horts post - thanks!

ReplyDeleteThank you Pat! :)

ReplyDelete