If you're ever in a room of soil scientists, I would recommend that you think twice before using the word "dirt". Dirt and soil are not the same thing (i.e., dirt is devoid of any life, while soil is teeming with life), and some people will get quite upset if you interchange the two words (for the record, I am not one of these people). Case in point: I happened to meet someone who had gone on a first date with one of my colleagues. He told me that the date was going well, but as soon as he used the word "dirt", my colleague's mood completely changed, the date quickly came to an end, and he never heard from my colleague again. So, if you want to make it to a second date with a soil scientist, make sure you're using the word "dirt" correctly...or maybe just don't use that word at all.

Anyways, perhaps you have a garden that is, quite literally, made of crummy, old dirt. Or, more likely, it's made of poor quality soil. Do you abandon all hope in having a healthy and fruitful garden? Do you scrap your life here and move to the Midwest in pursuit of more fertile soil??? No! There is another way to attain a thriving, productive garden, and that is through the regeneration of your soil.

Soils can generally be characterized by two things: soil texture and soil structure. Soil texture refers to the proportion of sand, silt, and clay within a soil. This proportion governs the characteristics of a soil, such as its nutrient-holding capacity, drainage rates, and affinity for compaction. I'm sure many of you will resonate with the challenges of highly clayey soils, which are prone to slow water drainage, limited oxygen availability, and compaction.

Unfortunately, there is no practical way to change a soil's texture at scale. The good news, however, is that a soil's innate behaviors can be adjusted by altering the soil structure, which refers to the arrangement of soil particles. Specifically, you want to promote the arrangement of your soil particles into aggregates.

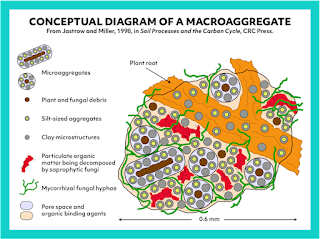

Basically, aggregates are clumps of soil particles that are bound together by organic matter, fungal hyphae, and roots. Not only do they increase the resiliency of soils to disturbance and create microhabitats that support diverse microbial life, but they also help increase water-holding capacity in sandy soils (organic matter acts like a sponge) and increase water/air infiltration in clayey soils (by increasing pore space).

- Incorporate organic matter into your soils using amendments such as manure, biosolids, plant-based compost, and/or coconut coir. The goal is to reach a soil organic matter content of 5% in your soils (contrary to popular belief, you don't want more than 5%). Take caution if applying organic matter amendments that are high in salts, such as manure and biosolids, as high salts can damage plants and soil structure. Before applying any organic matter amendment, it's best to do a soil test on your garden soils to understand the current levels of organic matter and salts present, which will inform how much amendment to apply.

- Grow cover crops when soils are bare (e.g., during the off-season). Cover crops will add organic matter into the soil through their roots, and they can be an additional source of organic matter if the cover crops, upon dying, are left on the ground or incorporated into the soil. Cover crops will also protect the soil from erosion and can add nitrogen into the soil if the cover crop is a legume.

- Mulch around your plants. Mulch will conserve soil moisture, help control weeds, and ultimately add organic matter into the soil as the mulch breaks down over time. Organic sources of mulch include wood chips, straw, or grass clippings. If using straw or grass clippings, take into consideration whether any herbicides have been used or if weed seeds might be present.

- Reduce disturbance of your soils. While some disturbance may be necessary when incorporating organic matter amendments, frequent or intense disturbances can ultimately degrade soil structure. As a result, consider using less invasive ways of amending (i.e., a broad fork instead of rototilling) and avoid tilling unless you're adding organic matter.